More Teens Need to Work

Done rightly, work experience complements classroom learning and matures teens.

Ben Sasse’s recent runaway bestseller emphasized the importance of teens working. Why? Because working teaches us the joy of producing — of being useful to others — as opposed to merely consuming the goods and services produced by others. At work, it’s about the team, and what you’re contributing. At school, it’s about you, and what you’re getting. A student consumes an education provided by his or her teachers — folks who don’t need you to perform like a boss does. Teachers get paid the same whether their students earn As or Cs.

Work is where teens are more likely to have their narcissism confronted.

So work is where teens are more likely to have their narcissism confronted. After all, working as a teen gives you a chance to fail when the stakes are relatively low. You’d rather make mistakes in part-time jobs, not in your first full-time gig. And it helps to receive clear correction when you fall short. While on the job, teens are typically surrounded by adults rather than peers. Over time, this has a maturing effect. Meaningful time with adults gives teens an enhanced vantage point with which to assess their young lives.

Teens Who Work Do Better

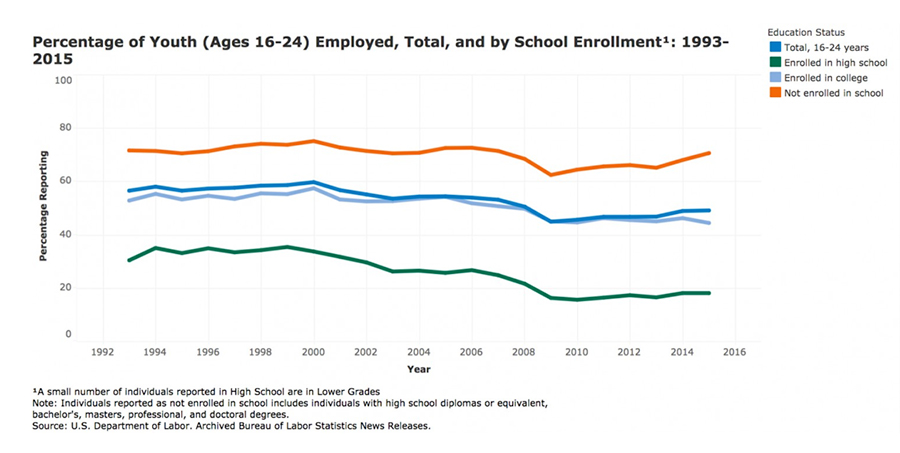

There are so many benefits to having a job when you’re young. But sadly, the number of teenagers employed while in school has dropped to less than 20 percent today, an all-time low since the U.S. started keeping track in 1948.

We need to rethink the conventional wisdom that says jobs are a distraction to a student’s academics. That may be the case if the job is more than twenty hours per week when classes are in session. But students with a moderate work commitment actually use their time better. So they academically outperform their non-working peers.

But What about College Admissions?

Another problem among high school teens is the perception that working won’t help with college admissions. A 2015 report from the National Association for College Admission Counseling showed that on a list of 16 factors considered in the admissions decision process, work was the least important factor. That’s a mistake, because academic success tends to flow from a student’s decisions more than their innate intelligence.

Character is formed through faithfulness to commitments, and the benefits of character often transfer from the workplace to the classroom. In fact, thinking you’re gifted can make you cocky — less likely to study, less likely to succeed, and more likely to be shocked when the low grades come in. (See also Angela Duckworth’s research on grit.)

While on the job, teens are typically surrounded by adults rather than peers. Over time, this has a maturing effect.

While admissions officers may not (yet) value work per se, they do value the writing sample. So teens can write about their work experience for their essay. With less than 1 in 5 teens ever having held a job, why not? Write about what you do in your job and how it helps your organization achieve its goals. Write about why you work, what you’ve learned from your work, and how your work relates to what you hope to do after college. Admission officers love hearing how an applicant’s experiences have contributed to the arc of their personal development.

Finding (or Creating) Work

Another reason so many teens don’t work is our slow-growth economy. Teens are sometimes competing with able-bodied adults for entry-level, low-skilled jobs. Couple that with advances in technology (automation) that have eliminated some jobs. It’s just tougher for teens to land that first for-pay gig.

So how can you overcome these obstacles? First, practice entrepreneurship and creativity. Identify skills and services you can perform. Then leverage your network (and family’s network) to spread the word. Offer one-time services as opposed to asking for an ongoing commitment. It’s natural that a family that has you clean their garage or paint a few windows may later think of other things you can do. A series of manual labor gigs can last a student a few months. Another benefit of self-employment is that you tend to have greater control over your work hours.

The bottom line is that an education shouldn’t be merely academic.

Secondly, consider volunteer work, particularly in something that lets you acquire a new skill. I began by observing the benefits of work. I didn’t even mention the paycheck. Any work that’s useful to others is good work. If you can get paid, great. If not, do it anyway, knowing that you’ll eventually get paid — by that employer or another. Development of work skills and experience is itself valuable.

The bottom line is that an education shouldn’t be merely academic. Done rightly, work experience complements (rather than competes with) classroom learning. It will make teens better at whatever they do down the road.

Dr. Alex Chediak (Ph.D., U.C. Berkeley) is a professor at California Baptist University and the author of Thriving at College (Tyndale House, 2011), a roadmap for how students can best navigate the challenges of their college years. His latest book is Beating the College Debt Trap. Learn more about him at www.alexchediak.com or follow him on Twitter (@chediak).